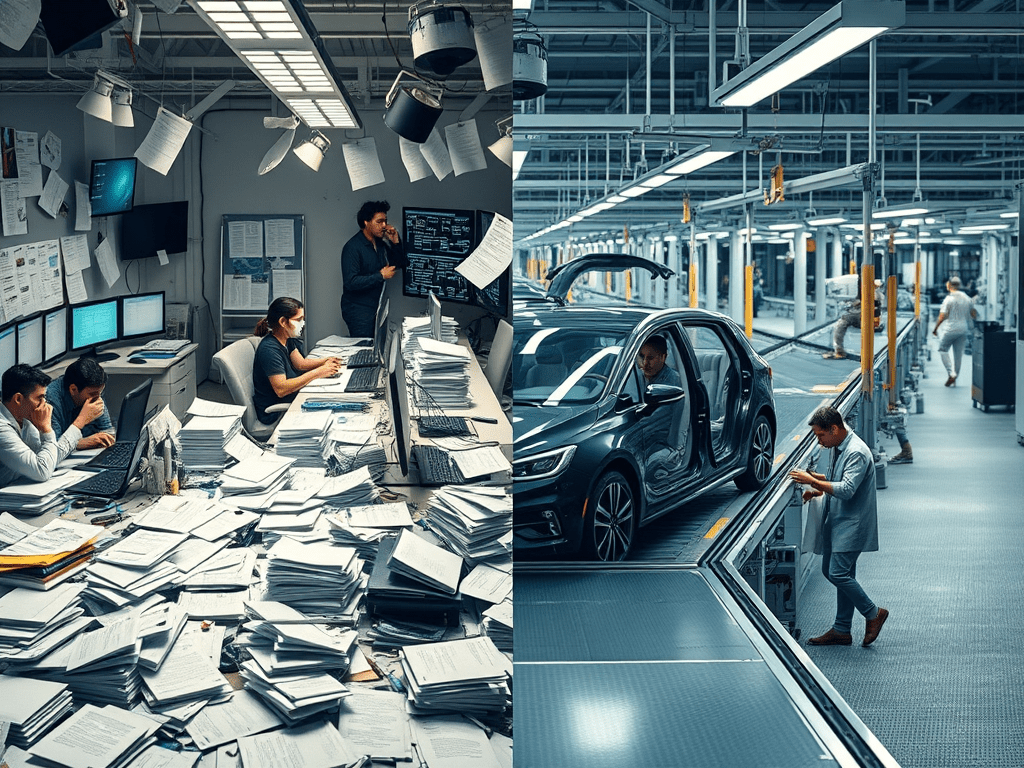

If I were to say to you, “You know what would be a great way to build a car? Put all the necessary parts in the middle of the factory floor, scattered around the chassis, then ask each person to grab their tools and come up and do their bit,” you’d think I was crazy.

And yet, this is how most knowledge work projects seem to be organised.

We plonk a project or a challenge in front of a group of people and say, “You’re a team now. Work as a team. But you’re autonomous and self-organised. Get the things you need, meet when you want, produce results.” And for some reason, we think that’s going to work well.

I know knowledge work is producing something different to a car. It’s often based on transferring hard-won skills, knowledge, experience and understanding, through deep thought, analysis, categorisation, and problem solving, into something outcome-based.

So why the parallel?

Because the current way isn’t working.

The breakthrough in the early twentieth century of the ‘Production Line’—where the team workers stayed still and pulled the car chassis to their station along a pre-determined production route when they had capacity—increased productivity many-fold. Scraping my memory banks, I think early cars used to take something like 12 hours to build in the ‘craft’ model (as I described in the opening). Come the Production Line, it was less than 1.5 hours.

Knowledge work is still fumbling around in the 12-hour mark. There hasn’t been, in many industries, the significant leap in productivity. Research from Asana shows that knowledge workers spend around 60% of their time on ‘work about work’, not productive tasks. Surprised? Me neither.

This is nothing to do with hybrid, remote or office working. This is nothing to do with four-day weeks. This is to do with clear outcomes, clear ways of working, and removal of distractions.

What Happened to Autonomy?

The term ‘knowledge work’ was first popularised by Peter Drucker in the 1950s and 60s. He later observed in the 1990s:

“Knowledge workers must be autonomous. They must know more about their job than anyone else in the organisation. For this reason, they must be responsible for their productivity and quality of work.”

— Peter Drucker, Management Challenges for the 21st Century (1999)

I propose a distinction between autonomous process and autonomous fulfilment—or, to put it another way, productivity and quality.

Autonomous, self-emerging productivity processes, in the current climate, seem to lead to people fumbling around, sending lots of emails, messages, and meetings. It isn’t clear who’s doing what or why. See Cal Newport’s definition of the Hyperactive Hive Mind, where unscheduled communication via emails and instant messages dominates the workday, undermining focus and flow.

— Cal Newport, A World Without Email (2021)

Process should be observed, crafted, and continuously improved. Like the Production Line.

How we get things done is where autonomy should remain—to ensure quality. When the work is in my court, let me work out how to play it to achieve the outcome to a high standard, using my skill as a knowledge worker.

A Lean-Inspired ‘Production Line’ for Knowledge Work

A great knowledge work ‘Production Line’ equivalent will come from Lean thinking. This could include doing things like:

- Map the steps currently taken from trigger/request through to value fulfilment.

- Limit how much work can sit in any one part of the process—less is more.

- Set entry and exit criteria to ensure quality at each step.

- Pull work into your step only when you have capacity—never push.

- Observe delays or bottlenecks (often approvals or key-person dependencies)—can you redesign, eliminate, or scale them?

- Continuously improve the system based on what you observe.

I’ve tried this many times over the years. I remember one Marketing team who did this and reduced the time it took to produce campaigns by about 20%, improved the quality, and were able to experiment more often to see what landed best with audiences.

It works.

So… How Is Your Organisation Running Knowledge Work Projects?

Is everyone standing around the work in the middle, trying their best but delivering little?

Or is your work flowing—clear, limited, and effective?

References

- Drucker, P. F. Management Challenges for the 21st Century (1999)

- Newport, C. A World Without Email (2021)

- Asana. Anatomy of Work Index (2022). https://asana.com/resources/anatomy-of-work

- Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. The Machine That Changed the World (1990)